A few weeks ago I had the privilege of joining the Main Line Singers to perform and share carols at a local assisted living community. When I started singing with the group in February, it had been a long time since I sang with such a large group—40+ years (when I traveled to Europe with American Music Abroad.) I had been wanting to find a group for a while and last February the stars aligned and I joined the group to prepare for our semi annual concerts—in June and February. We are now 100 members strong and I have that special thrill that vibrates through me when we are in full form. It’s been a true pleasure to have in a year where much of the news has been challenging and, often, grim.

Before Christmas we headed to bring our brand of fun to a group of seniors…we were about 30 strong and it’s always gratifying to see faces light up as we launch into a familiar tune.

I’ve always enjoyed singing—as children all of the Shillingfords were in church and school choirs and we all sang through high school. When I graduated from high school I was fortunate to travel with a group of remarkable singers through Europe—singing in town halls and churches in Germany and Holland, outdoor amphitheaters in Austria and Notre-Dame de Paris in France—what a thrill that was!

Christmas always afforded opportunities to share the gift of joy in singing—at church and in school, at our local carol sing, and, occasionally, door to door in a time when people used to do that.

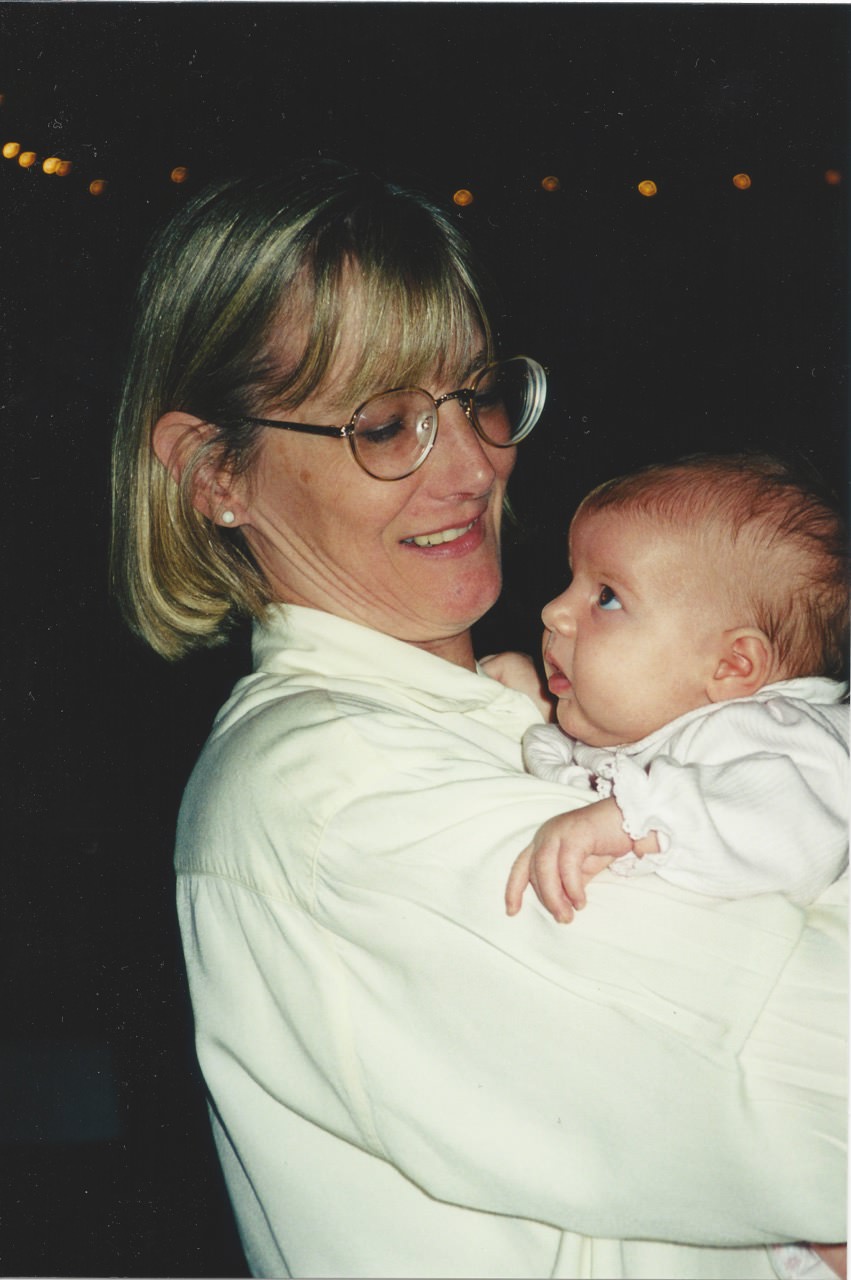

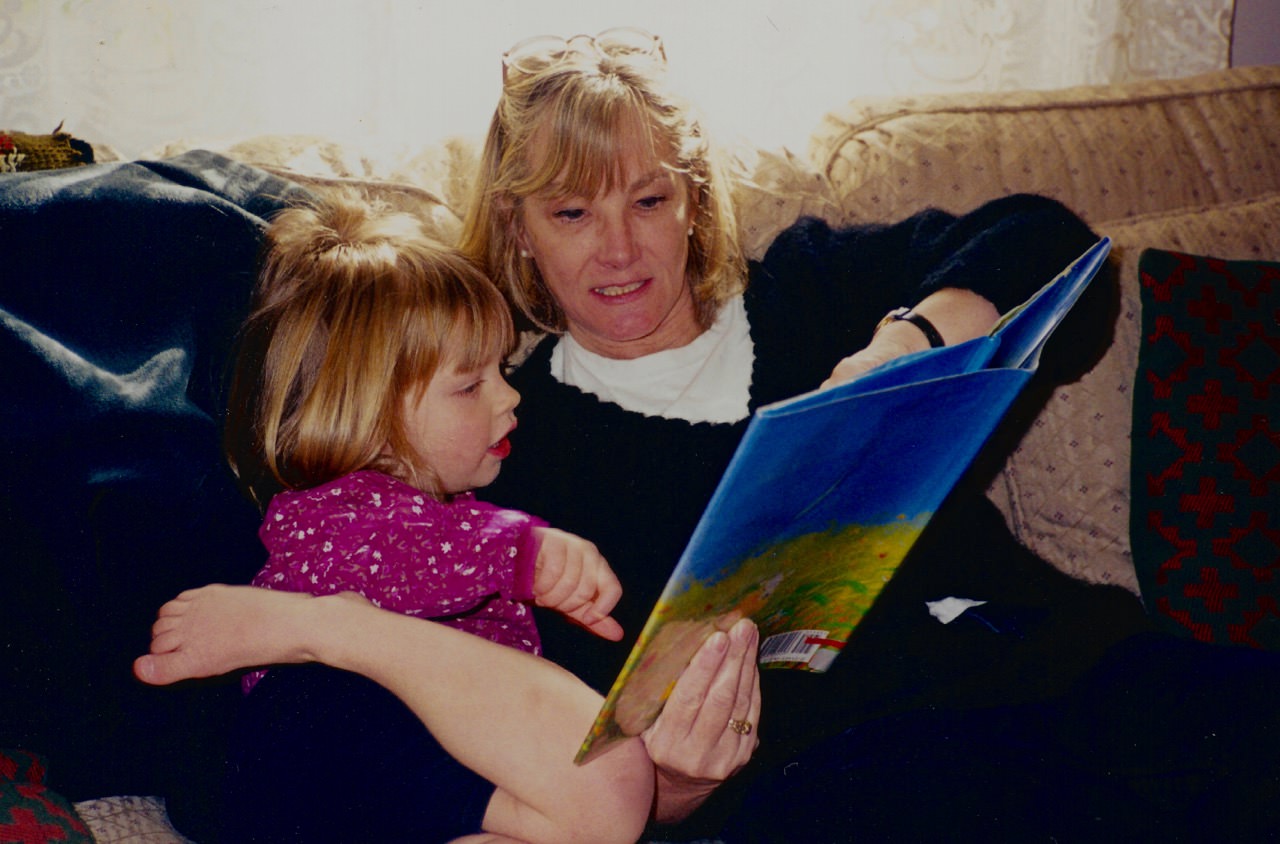

And singing was part of our family life—when we traveled we often sang in the car—sometimes in harmony to songs that we knew. My parents were both in the church choir—Mom still sings with the choir at her retirement community—in my memories I can hear dad in the basement as he worked on the annual handmade House of Shillingford gift every year singing to the Bass part of whatever piece they were working on for Christmas—Bach or Mozart, Rutter or Handel (in fact I can still hear his voice singing the Hallelujah Chorus whenever that song is performed.)

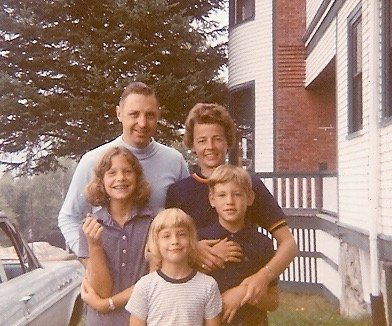

So, I thought nothing of it when, every year as a child, my mom would load my sister and brother and I to drive out to Immaculata College where she worked as Assistant Athletic Director, to sing for the nuns. We would dress up, drive out to Malvern, walk into Villa Maria Hall with its great rotunda and huge Christmas tree, visit the offices of all of the administrators and deliver our homemade gifts to them and then go and stand at the tree and sing carols—my mom providing harmony, my sister, Anne, singing descants that she knew, Rob providing tenor support as his voice hadn’t changed, and me at 10ish singing the melody. The nuns and staff would all come out of their offices and listen from the balconies and would clap politely when we were done. I have no idea how we sounded—it’s a huge space to fill with four voices but the reverb is pretty amazing, so maybe that helped.

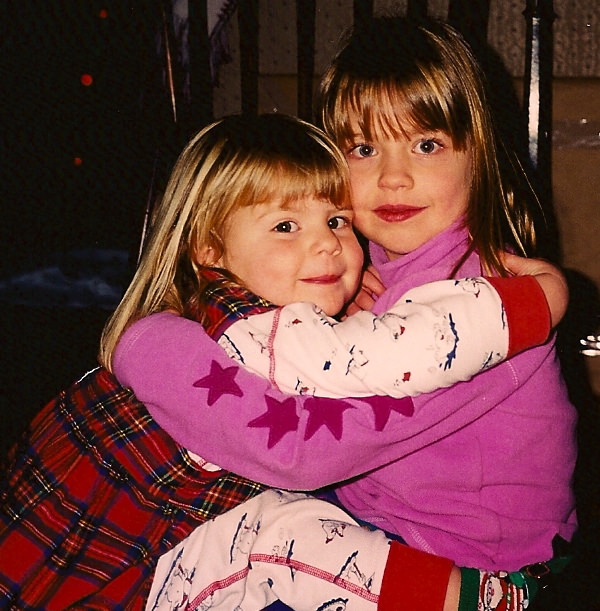

Truly, it wasn’t until I had kids of my own that I realized how unusual this whole thing was—there is no way that my kids, even in their most obedient times, would agree to sing with me alone in front of anyone, let alone a bunch of strangers. And I look at my sister and brother, who are older than me and wonder how and why they were coerced into performing. At my age, I loved it—I was a little bit of a ham and always enjoyed playing to a crowd, so it was a fun adventure. Sometimes I think, “well, it was a simpler time, people did these things,” but the truth is none of my friends or acquaintances in all the years I’ve shared this memory ever said, “oh yeah, we did that as kids, too!” So I’m thinking it was pretty unique. Honestly, I don’t know what motivated Mom to do it, because I for sure would not want to sing in front of my colleagues.

Nevertheless, it remains a part of the Shillingford Family lore and now a sweet, if a little baffling, memory of my childhood.

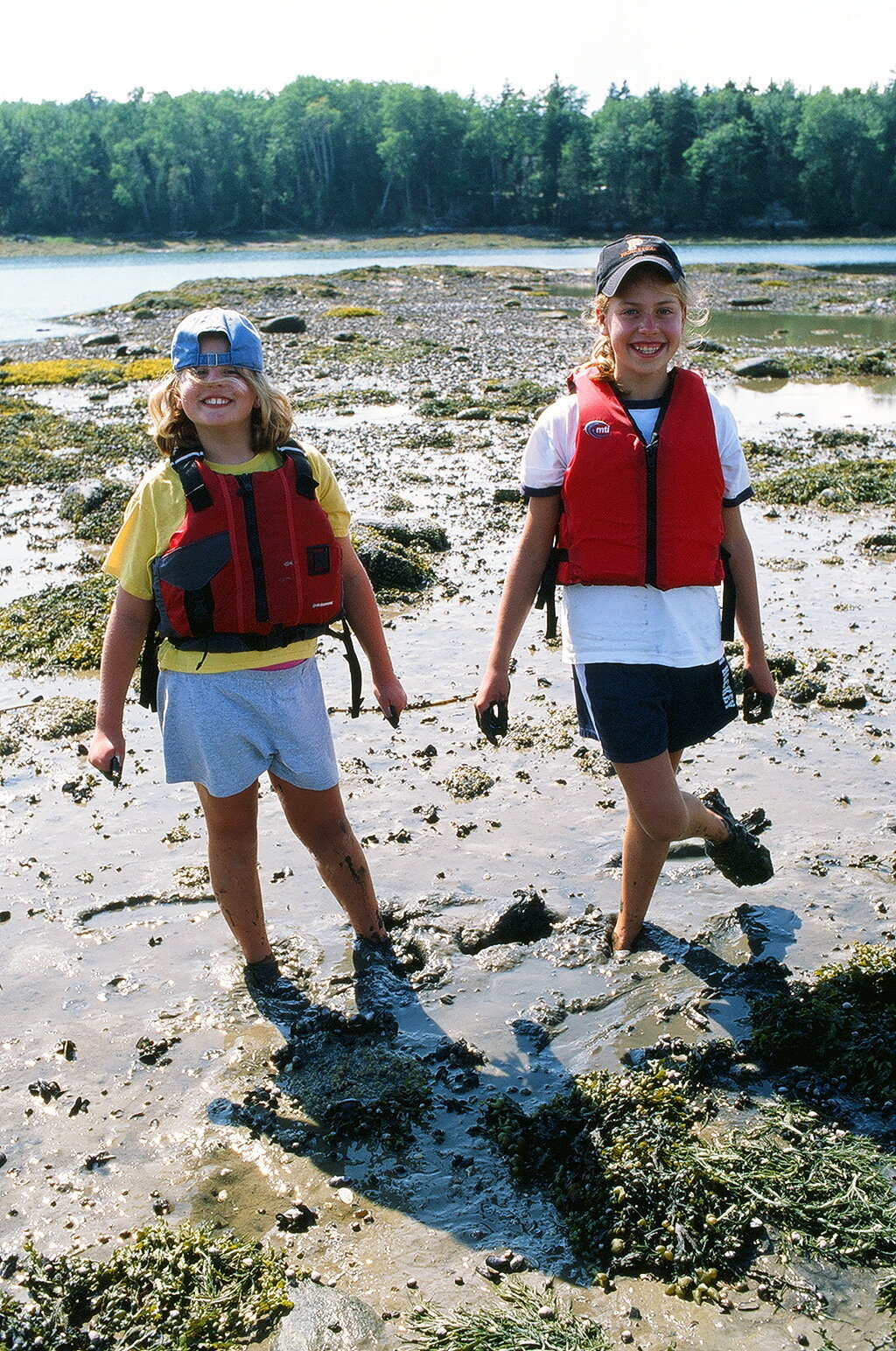

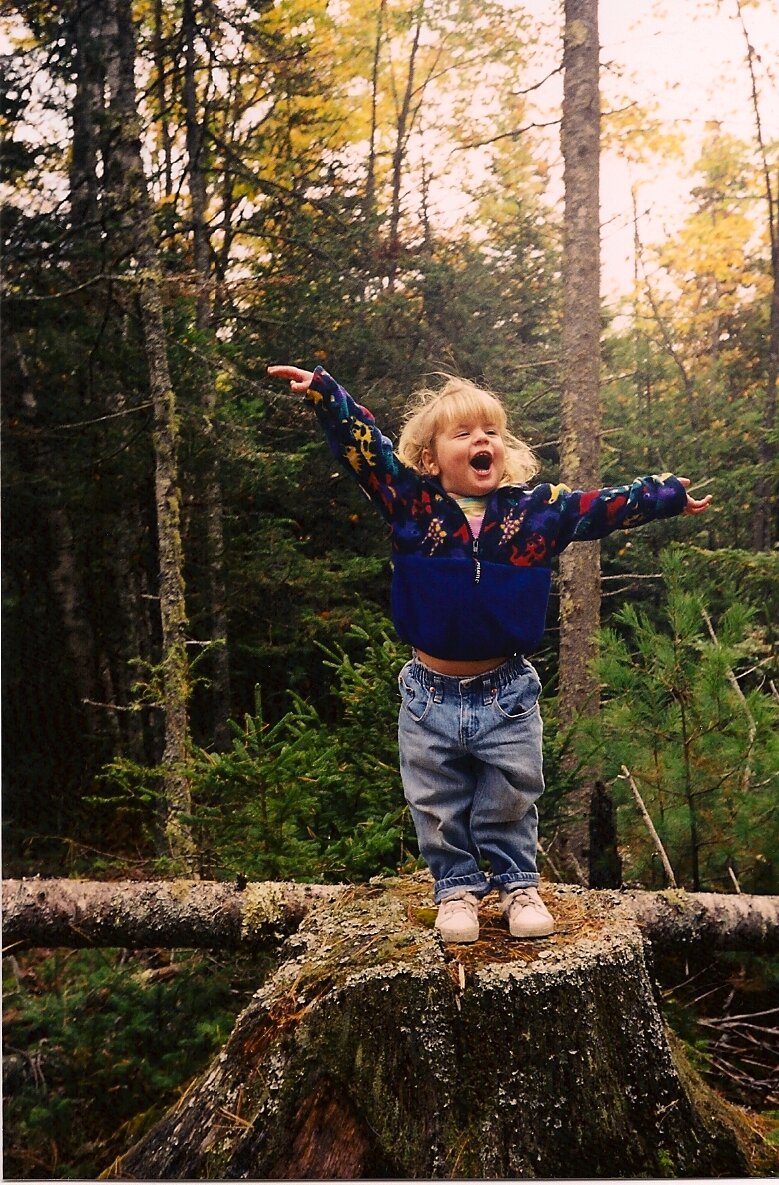

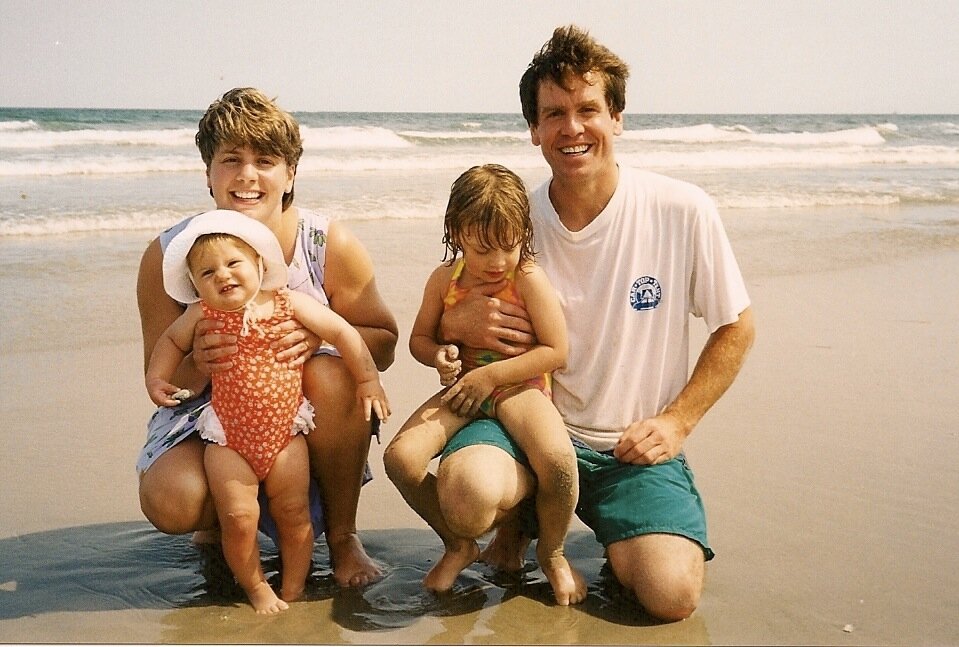

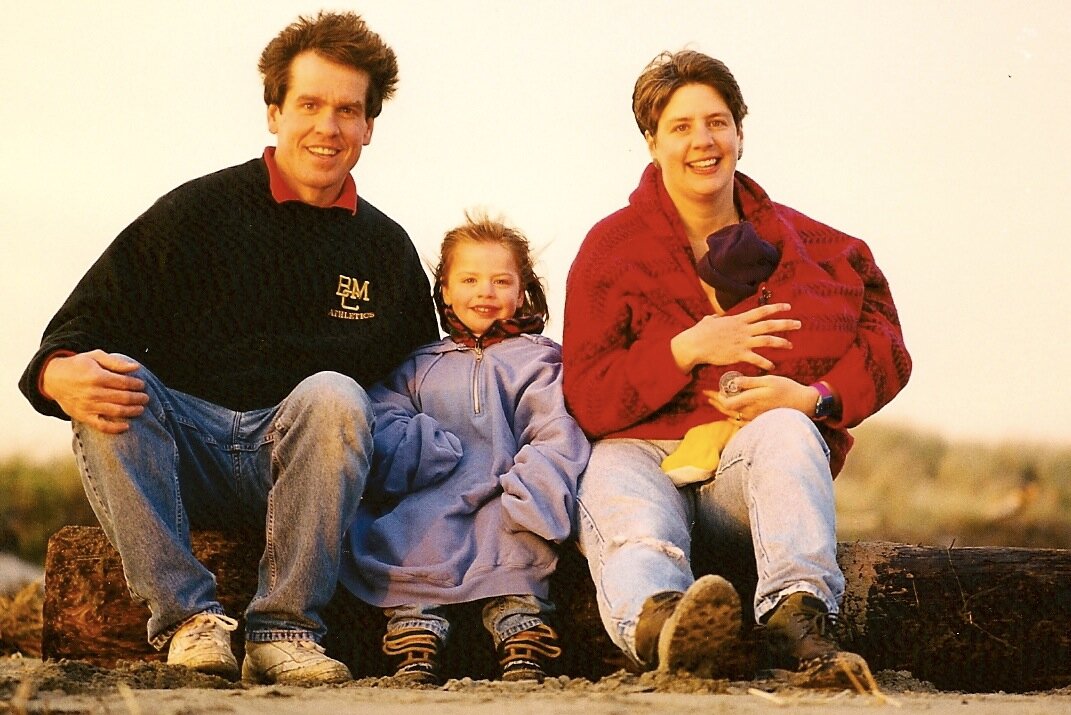

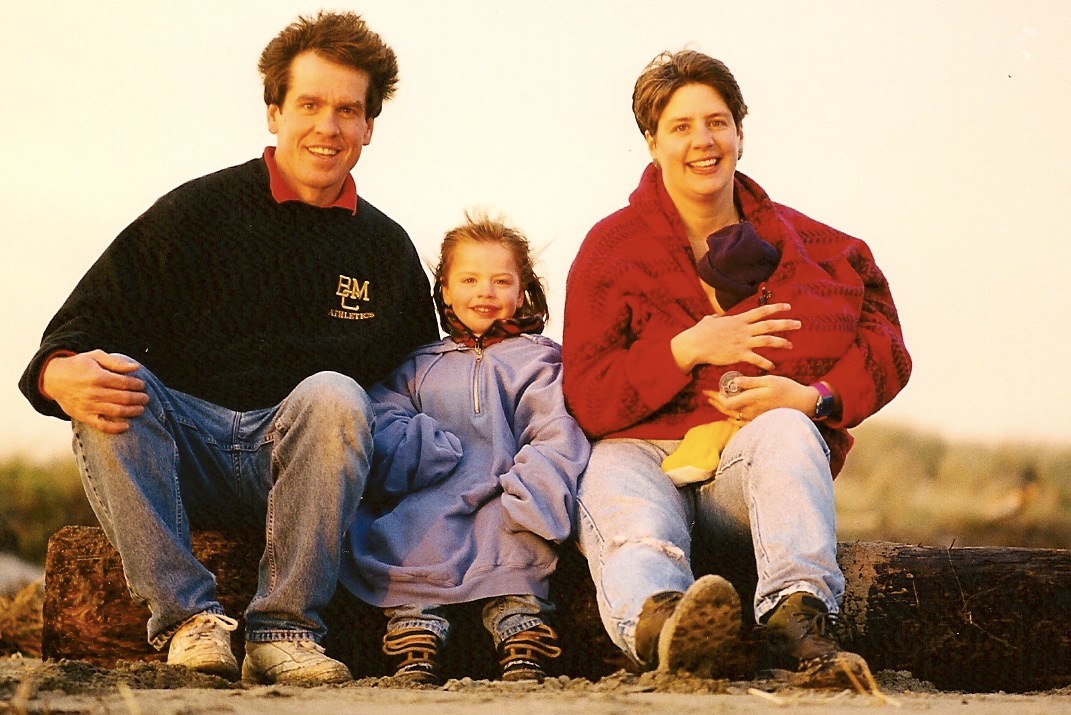

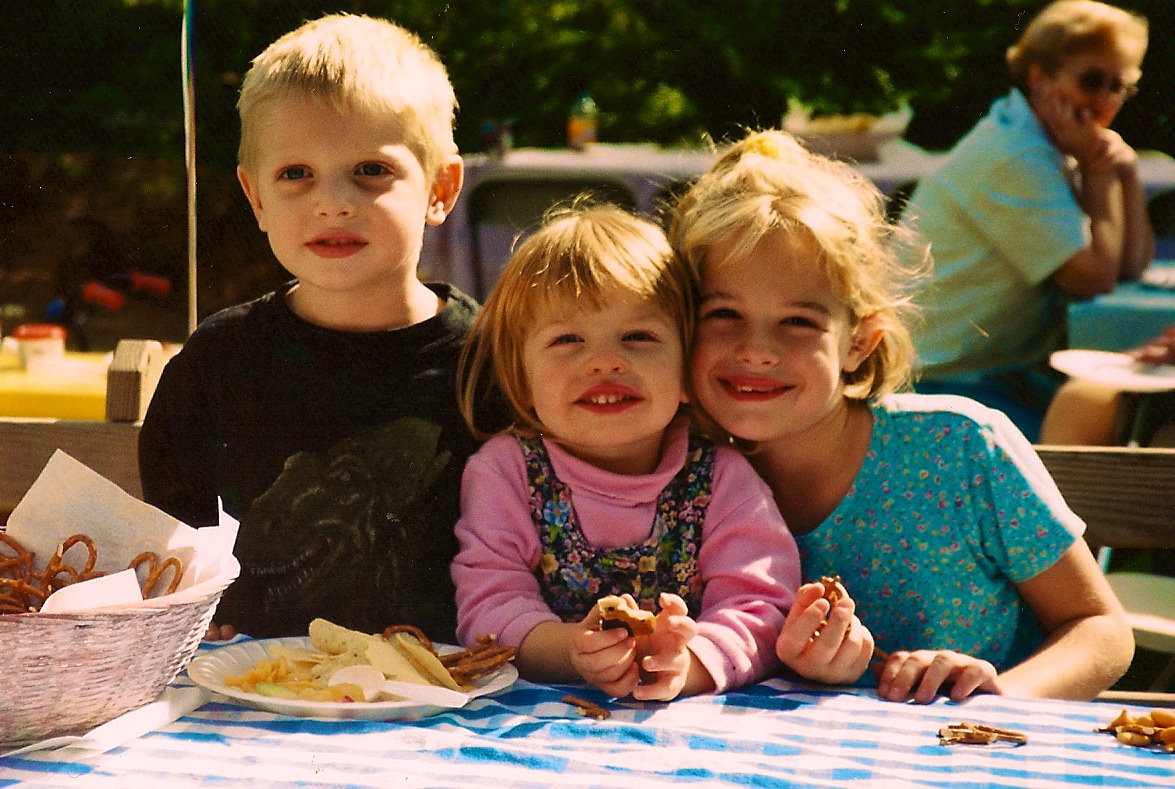

But the true gift was the joy of shared song—the love of a beautiful harmony, of wonderful melodies that can transport me to times in my life, familiar and joyous and sometimes melancholy, but always special. These songs and memories resonate through my family’s lifetime and David and I have passed a love of music and singing on to our girls. Recalling these songs and times, it always goes back to those days in the car singing together, whether to the radio or on our own and then to choir and chorus and the shared exhilaration of joyous voices raised in song.

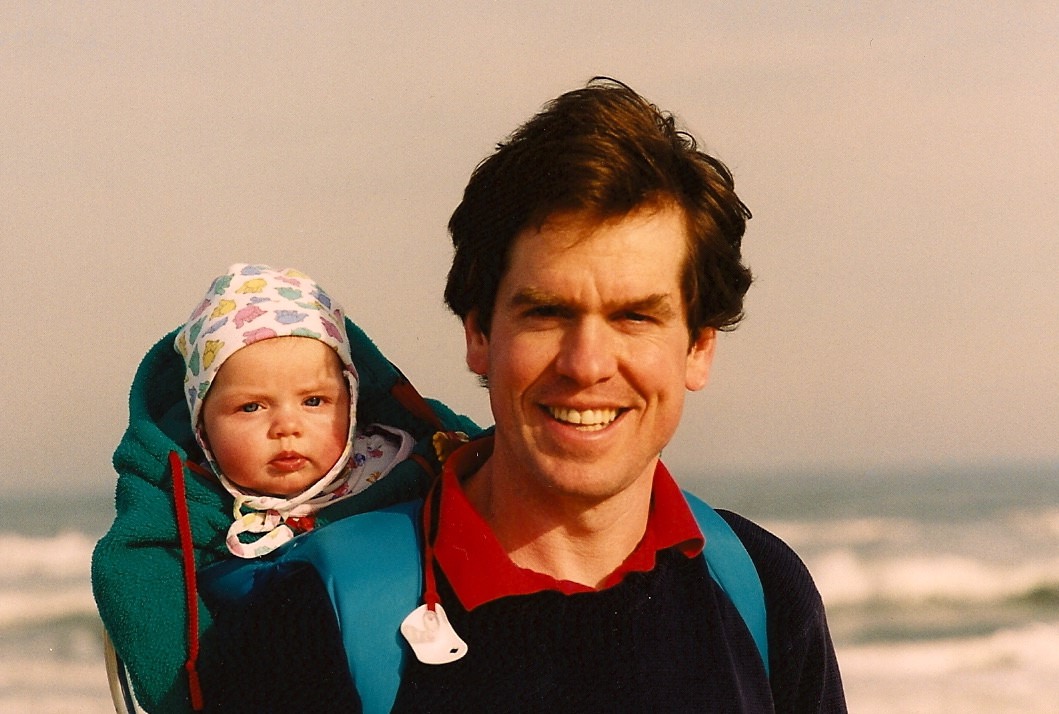

Post Note: In 2021, we decided to play it safe and forego a big family gathering for Christmas. We opted to bring some holiday cheer to my parents by caroling for them at their retirement community. I treasure this video for all it represents.